Researchers have discovered a way to view synthetic nanostructures and molecules using a new type of super-resolution optical microscope that does not require fluorescent dyes, making it a practical tool for use in biomedical and nanotechnology research.

“This super-resolution optical microscope has opened a new window on the world of nanoscopy,” said Ji-Xin Cheng, an associate professor of engineering and biomedical chemistry at Purdue University. Conventional optical microscopes can see objects no smaller than 300 nanometers (1 nanometer is one billionth of a meter), which is a limit known as the “diffraction limit”. The diffraction limit is defined as half the wavelength of light used to view the specimen in a microscope. However, researchers hope the microscope can be used to view molecular structures such as proteins and lipids, and also synthetic nanostructures such as nanotubes that have diameters of several nanometers.

“This super-resolution optical microscope has opened a new window on the world of nanoscopy,” said Ji-Xin Cheng, an associate professor of engineering and biomedical chemistry at Purdue University. Conventional optical microscopes can see objects no smaller than 300 nanometers (1 nanometer is one billionth of a meter), which is a limit known as the “diffraction limit”. The diffraction limit is defined as half the wavelength of light used to view the specimen in a microscope. However, researchers hope the microscope can be used to view molecular structures such as proteins and lipids, and also synthetic nanostructures such as nanotubes that have diameters of several nanometers.

“The diffraction limit represents a fundamental limitation of the resolution of optical imaging,” Cheng said. “Stefan Hell of the Max Planck Institute and others have developed a super-resolution imaging method that requires fluorescent tagging. Here, we demonstrate a new scheme that breaks the diffraction limit in optical imaging of non-fluorescent specimens. "Because it is marker-free, wave signals from objects can be directly detected so we can study these nanostructures further."

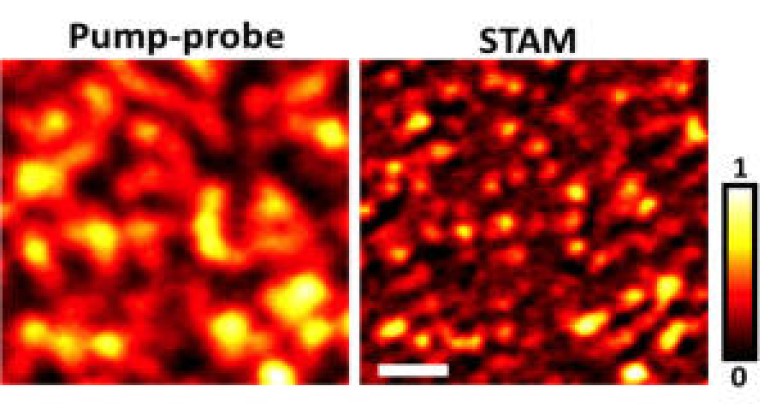

A detailed explanation of this discovery is discussed in a research paper that appeared on Sunday (28 April 2013) in the journal Nature Photonics. This imaging system, called saturated transient absorption microscopy (STAM) uses a trio of laser beams, including a donut-shaped laser beam that selectively luminesces only certain molecules. The electrons in the atoms of the glowing molecules momentarily move to a higher energy level, also known as the excitation process, while the other electrons remain in the ground state. The image of the object is formed using a laser that can compare the differences between molecules in the excited state and the ground state.

The researchers demonstrated the microscope system by taking images of graphite nanochips that are 100 nanometers wide. This system has great potential in the study of nanomaterials, both natural and synthetic. Future research will likely include lasers with shorter wavelengths. When the wavelength of light shortens, researchers can examine smaller objects in a more focused manner.

Source: chem-is-try.org